Status of primary care system keeps slipping

DATE: May 16, 2024

More and more doctors leaving practices, some cancer screenings down

- Jennifer Smith, Commonwealth Beacon, Thursday, May 16, 2024

BY ALMOST EVERY almost every significant metric, primary care in Massachusetts is moving in the wrong direction, according to a new report. The system is now bleeding primary care doctors faster than the national rate, bellwether screening rates for some cancers are down, and demographic disparities in accessing care remain.

The Center for Health Information and Analysis and Massachusetts Health Quality Partners unveiled a primary care dashboard on Thursday to track the situation, and officials from both organizations sounded alarm bells at the initial findings.

“Things have gotten so much worse, and we’ve heard a lot from the public about particularly access issues,” said Barbra Rabson, president of the nonprofit Massachusetts Health Quality Partners. “And of course the dashboard reinforces that access has gotten a lot worse. And these other structures that we look at have also gotten worse. So, it wasn’t a great picture to start with, and we’re sort of continuing on that trend, unfortunately.”

According to the dashboard, 5.6 percent of physicians left primary care in Massachusetts in 2021, an increase from 3.1 percent in 2019 and well above the national rate.

The dashboard is both a data project and a policy project, to give clear metrics on the state’s primary care system. “In about 2018, MHQP became very aware of how fragile primary care was,” Rabson said.“And then the pandemic hit and things got worse, and then we realized there was no place to go to see, ‘well, where are they now?’”

Primary care spending has been a flashpoint in health care spending debates on Beacon Hill. The underfunded and shrinking field caused patients to rely on hospitals for care needs they would have addressed with their primary care physician, especially during the height of COVID-19, Health Policy Commission Director David Seltz said during a health care cost growth hearing this spring.

The new dashboard tracks primary care finance, capacity, performance, and equity. This interaction includes childhood immunization status, and medical school graduates entering the primary care field.

It also includes the percentage of residents who have a primary care provider as part of their plan design. That proportion dropped between 2020 and 2021, from 49.9 percent to 48.6.

Even with prompt policy action, there wouldn’t necessarily have been a rapid change in outcomes over a single year, noted Lauren Peters, executive director of CHIA, the independent state agency and primary hub of health care data and analytics for Massachusetts. But the worsening landscape was an unwelcome surprise.

“When we look at the two years, I would hope that some of the dynamics, some of the numbers driving the low rates of screening in 2021 were negatively impacted by the pandemic, and we would at least have expected by 2022 that these things would have have potentially rebounded or gotten better,” Peters said. “And that is not what we saw in a number of the screening areas.”

Screening rates can indicate access and availability, she said.

Between 2018 and 2022, cervical cancer screening rates dropped by 5.2 percentage points, to just over 81 percent, and colorectal cancer screening rates for those over 50 dropped by 2.5 percent. Breast cancer screenings for women over 50 rose by about 3 percentage points, hitting almost 85 percent.

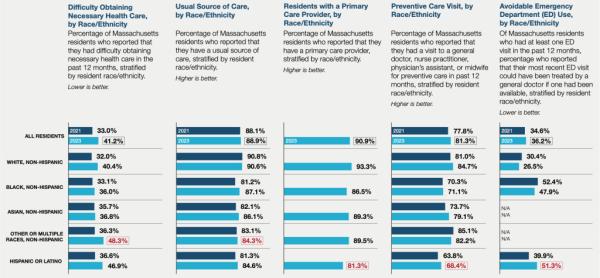

Health advocacy groups have long tracked racial and regional disparities in care, but the issues are becoming more widespread, Rabson said.

“We know that there’s a lot of racism in the healthcare system, and we see different racial and ethnic groups using or not using services more or less,” she said, so data showing that non-White residents are less likely to say they have regular sources of care or primary care providers “wasn’t a surprise.”

In 2023, however, White residents were more likely (at about 40 percent) to say they had difficulty accessing care than Black or Asian residents, though nearly half of Hispanic or Latino residents reported difficulties with obtaining necessary care.

“Anecdotally, we’ve heard that Western Mass. has been having a harder time in terms of access and utilization compared to Eastern Mass.,” Rabson said, “It used to be like we talked about it in pockets, but now it feels pretty statewide,” she said of the primary care access issues. “There are some differences, but there’s declines all over the state.”

While Massachusetts does boast high rates of coverage, that does not always translate into regular care. The new dashboard, which includes an interactive version, finds that 90.9 percent of the state reported having a primary care provider at the time of the 2023 survey, yet the percentage of patients who reported that they had difficulty obtaining necessary health care in the past 12 months rose. In 2021, about 33 percent of residents said they had difficulties obtaining care, which climbed to 41.2 percent in 2023.

Primary care spending represented 6.4 percent of overall medical spending across all insurance categories in 2022, according to the report.

Spending on commercial primary care services was $995.2 million that year, just 6.7 percent of the category’s total medical spend. Under MassHealth plans, $208.1 million, or 7.5 percent of spending in the category, went to primary care.

“In terms of policy action, as a starting place, we as a system need to value primary care more,” Peters said. “We need to make more investments and really move the needle on that 6.4 percent number.”

In its 2023 Cost Trends Report, the independent Massachusetts Health Policy Commission built on CHIA’s initial report and corroborated the primary care spending trends.

“Primary care spending continues to grow more slowly than other categories of medical spending,” the report noted. The authors later wrote that prior research found that, “among commercially insured residents, those living in lower-income communities were more likely to go without medical care. This pattern remains true for primary care.”

Those differences were especially stark among children. Almost 11 percent of commercially insured children in low-income zip codes lacked any primary care spending, more than double the rate in the highest income zip codes.

Spending is “the driver of a lot of the trends that we’re seeing,” Peters said, “because if we as a system are not valuing and investing in primary care, we are going to continue to see the primary care physicians leaving at a higher rate. We’re going to continue to see the gaps in access. We’re going to continue to see folks using the emergency department for non-emergency type services, because there’s not the staff or the overall sort of capacity in the system to absorb the demand for primary care.”